This report is intended to provide a high level overview of nutraceutical regulatory trends in the US and abroad with snapshots from Europe, Japan, Israel, China, India and Latin America including Mexico and Brazil. However, it should be noted that the nutraceutical regulatory environment is evolving and remains murky as the number of nutraceutical products continues to expand internationally and local agencies, working with international trade associations, struggle to harmonize regulations across different jurisdictions to ensure consumer safety while also creating a level playing field for competition. Our hope is this report will serve as an introductory guide for industry insiders with designs on going international as well as the financial community trying to better understand sector trends and valuation. Increasingly nutraceutical companies will be forced to navigate a wide range of different local regulatory requirements as regional players seek the global scale necessary to compete.

Key Takeaways

* Generally the goals of nutraceutical regulation have been focused on safety and labeling with lesser emphasis (as compared to pharmaceuticals) on product claims and intended use. This is achieved through Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations and a recent increase in enforcement.

* Consumers are largely responsible for determining the usefulness and value offered by nutraceutical products, although regulatory agencies are increasingly enforcing industry requirements that call for nutraceutical companies to track adverse events.

* There is consensus among nutraceutical companies that increased regulation related to quality and safety will benefit the industry, and help mitigate the risk of regulatory backlash if scrupulous players engage in abusive practices and are left unchecked.

* Greater enforcement of GMP regulations are likely to drive further consolidation in the relatively young, fragmented industry as those lacking proper scale are unable to comply with the greater emphasis on regulation or make the necessary investments to become compliant across multiple jurisdictions.

The Nutraceutical Market

Bourne Partners released an April 2013 Nutraceutical Sector Report (free download) that put the global nutraceutical market at $142 billion in 2011. With an estimated growth rate of 6.4% (CAGR), the market is expected to reach $204.8 billion by 2017. Growth is being driven by favorable demographics, increases in disposable income, rising healthcare costs and an increasingly robust OTC market. In developing nations, the middle classes are growing, which translates to increased disposable income because of typically regressive tax structures. Also, developing nations are increasingly becoming the preferred source for cheaper raw material supply found in many nutraceutical products.

Classifications and Definitions

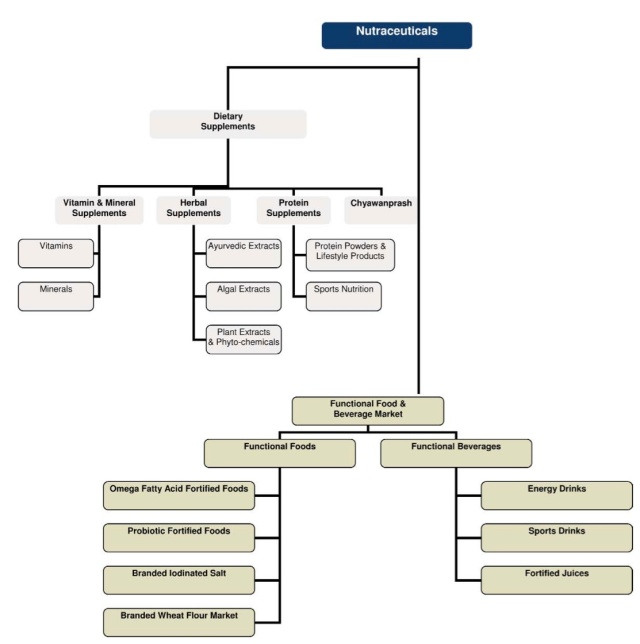

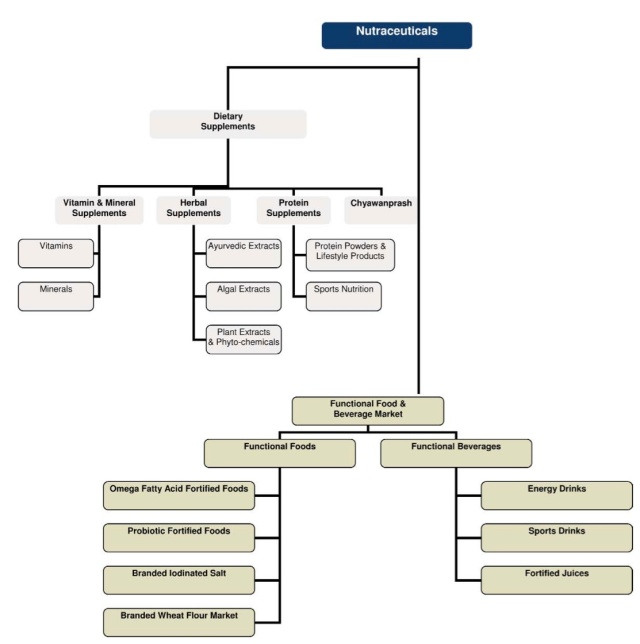

Part of trying to better understand the regulatory environment begins with defining nutraceuticals, which are also referred to as dietary supplements – a term preferred by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For the purposes of this discussion, nutraceuticals can be thought of in a broad sense as a food, food derivative or food product, usually in extracted form, that reportedly provide health or medical benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease. Such products may range from isolated nutrients, dietary supplements, herbal products and specific diets to genetically engineered foods and processed or supplemented “functional” foods such as cereals, soups, and beverages. Often used interchangeably to describe “nutraceuticals” are “dietary supplements”, which include vitamins, minerals, herbs, botanicals, amino acids, fatty acids and probiotics. For the purposes of this discussion, we will use nutraceuticals to refer to all of the above categories. The below chart from Frost & Sullivan’s report, “Global Nutraceutical Industry: Investing in Healthy Living,” provides a helpful overview of the different nutraceutical classifications:

Source: Frost & Sullivan and FICCI

All together, nutraceuticals represent a wide range of health products, and with a patchwork of local regulatory oversight and no global standards for compliance, those in the industry struggle to make distinctions between the ever growing number of nutraceutical categories. For example,

How might regulatory agencies distinguish between dietary supplement tablets and conventional foods with dietary, or “functional,” ingredients?

Is an energy drink a dietary supplement or a beverage? What are the ramifications for ingredient disclosure requirements? (Read more about the Monster Energy drink reclassification here).

How do specific cultural requirements for nutraceutical products vary from market-to-market in the east versus the west?

These are just some of the challenges facing a rapidly growing industry with varying product definitions and a collection of non-unified regulatory policies. However, what remains constant is the continued global demand for nutraceutical products as life expectancy increases and consumers take greater interest in their personal health.

Regulation Background & Recent Trends

Nutraceutical foods are not subject to the same testing and regulations as pharmaceutical drugs. The aim of nutraceutical regulation is largely to ensure products are safe and properly labeled. It’s important to note that nutraceuticals do not face the same level of scrutiny as pharmaceuticals in regards to product claims and intended use. There is a perception that this lack of oversight leads to products of variable quality and with claims of questionable merit. Unfortunately for the nutraceutical industry, this perception was reinforced in an April 2013 Research Letter published online in JAMA Internal Medicine. As reported in the letter, FDA data showed supplements were involved in half of all drug recalls. More specifically, 51% of Class I recalls over a 9-year period involved adulterated dietary supplements instead of a pharmaceutical product. Sexual-enhancement aids were the most commonly recalled product (40%), followed by body-building (31%) and weight-loss products (27%). Nine out of 10 (89%) supplement recalls occurred after 2008, and unapproved drug ingredients were involved in all of the supplement recalls. The study was limited since it only accounted for Class I recalls, and was unable to associate the use of many adulterated supplements with adverse events. Also, it should be noted that the increase in recalls coincides with an initiative by the FDA to increase inspections. Whether the recalls are the result of greater enforcement or a lack of compliance (or both), the findings reinforce the notion that the industry lacks oversight. Without improved self-policing and harmonized international standards and policies, the industry risks a regulatory backlash that could see nutraceuticals regulated with the same rigor as pharmaceutical drugs.

For the purposes of this discussion, we will focus primarily on policies relating to GMPs with an emphasis on overseas regulation. As noted in the above research letter, nearly a quarter (24%) of the recalled supplements were manufactured outside the U.S., a concern given that manufacturing practices in foreign countries are not held to the same regulatory and enforcement standards as seen in the US, Europe and Israel. However, not all of the blame falls overseas. The FDA has found GMP violations in at least half of the domestic dietary supplement firms it has inspected. Finally, we will close by briefly addressing areas of regulation that fall outside of GMP. This includes product claims, intended use, marketing and safety, which are discussed in their own section at the end of this report.

US Regulatory Agencies & Polices

Currently the FDA regulates dietary supplements under its own set of unique regulations, summarized here, that differ from those covering “conventional” foods and drug products. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA):

* The manufacturer of a dietary supplement or dietary ingredient is responsible for ensuring that the product is safe before it is marketed; and

* The FDA is responsible for taking action against any unsafe dietary supplement product after it reaches the market.

However, the absence of consistent enforcement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and globalization of supply sources has contributed to perceptions of significant safety loopholes. Perhaps not surprisingly, it was the nutraceutical industry that pushed both the FDA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement good manufacturing practices (GMP). Before then, the industry was largely self-policed, as it currently is with regard to product claims and intended use (see below), by its own trade association (Natural Products Association). However, with the introduction of the federal Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations (21 CFR, Part 111) in 2007, the FDA and HHS assumed oversight of GMP enforcement. Under the rule, all domestic and foreign companies that manufacture, package, label or hold nutraceuticals, including those involved with testing, quality control, and nutraceutical distribution in the US, have safety-related responsibilities, including, but not limited, to the following:

• assuring the safety of the ingredients used in their products, both before and after introduction to the market;

• evaluating the identity, purity, quality, strength, and composition of dietary supplements;

• preparing, packaging and holding products in compliance with FDA’s current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) regulations; and

• submitting reports to FDA of serious adverse events.

These requirements were implemented to avoid wrong ingredients; too much or too little of a dietary ingredient; improper packaging; improper labeling; or contamination problems due to natural toxins, bacteria, pesticides, glass, lead, or other substances. For their part, the FDA monitors nutraceutical products by reviewing adverse event reports, obtaining information from inspections of dietary supplement manufacturers and distributors, reviewing consumer and trade complaints, performing laboratory analyses of product samples, and monitoring retail outlets, including the Internet. There are also third-party GMP certifications and inspections, specifically those done by recognized organizations such as NSF International, the Natural Products Association (see above), and the U.S. Pharmacopoeia – all of which play an important role in overseeing industry GMPs.

A more detailed discussion of the 21 CFR, Part 111 requirements is provided by Nutraceuticals World here, and a description of the rule’s most relevant subsections is provided here. Also, Pharmavite, the maker of Nature Made® nutraceutical products, provides this infographic, which serves as a good overview the US regulatory process and includes a guide to the different sections found on a typical nutraceutical label.

In terms of regulatory trends, there’s a consensus within the industry that the FDA has thus far been focused on facility acceptability and manufacturing practices, with less attention paid to testing products, including ingredients supplied from overseas manufacturers. However, as regulatory efforts continue to ramp up, attention is expected to shift more to products and product label compliance.

With regard to adverse events, Congress passed legislation in 2006 that requires the regulator to collect consumer complaints of illnesses, medical complications and death (i.e., serious adverse events). It is the responsibility of the manufacturer, packer, or distributor – whose name appears on the label of a dietary supplement marketed in the US – to submit to the FDA any serious adverse event reports associated with use of the dietary supplement marketed in the US. From 2008 to 2011, the FDA received more than 6,300 nutraceutical-related “adverse event reports” (AERs), according to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

To help ensure companies are compliant with cGMP and adverse event reporting (AER) requirements (e.g., submitting serious AERs, maintaining AER records, and including firms’ contact information on product labels), the FDA increased its inspections of nutraceutical companies and took some actions against noncompliant manufacturers. According to the same GAO report, the FDA increased inspections from 120 in 2008 to 410 from January 1 to September 30, 2012. Over this period, the FDA took the following actions: 3 warning letters, 1 injunction, and 15 import refusals related to AER violations, such as not including contact information on the product label or submitting a serious AER.

As evidenced by the 15 import refusals, a major focus of FDA enforcement has been on ensuring the quality of imported raw materials while also increasing inspections of domestic manufacturers, including small and medium-sized manufacturers that often avoided the earlier attention of the FDA. However, the agency has raised concern that the recent budget sequester may result in fewer inspectors and a return to pre-initiative inspection rates.

There has also been a push by Senate Democrat Dick Durbin to reintroduce the Dietary Supplement Labeling Act, which would require companies to give the FDA the name of each supplement they produce, along with a description, a list of ingredients and a copy of the label. Sen. Durbin has used recent reports of adverse events associated with energy drinks to highlight the need for greater ingredient disclosure requirements in an effort to better inform consumers of potential risks associated with nutraceutical products (or in the case of Monster energy drinks, a newly classified beverage).

Legislation and policy relating to the nutraceutical industry is at a critical point. The popularity of the products along with the perception of minimal oversight and variable quality, has put the industry in the spotlight. Obviously a shift towards regulation more in line with pharmaceuticals would dramatically alter the global landscape. Tell us what you think:

Should the FDA take a larger role in oversight of the domestic nutraceutical industry?

Visit the Bourne Partners “Pharma and Healthcare M&A” group on LinkedIn to vote for how you believe the industry should be regulated by the FDA.

European Regulatory Agencies & Polices

In the European Union, food legislation is largely harmonized under the European Food and Safety Authority (EFSA). The legislation focuses on “food supplements”, which the Europeans define as concentrated sources of nutrients (e.g., proteins, vitamins and minerals) and other substances that have a beneficial nutritional effect. The main EU legislation is Directive 2002/46/EC related to food supplements. The EU maintains a list of permitted vitamin or mineral substances which may be added to food supplements for specific nutritional purposes. Vitamin and mineral substances may be considered for inclusion in the lists following the evaluation of an appropriate scientific dossier concerning the safety and bioavailability of the individual substance by EFSA. Companies wishing to market a substance not included in the permitted list need to submit an application to the European Commission. New products originating from Europe are presumed to have passed these stricter European development and quality requirements. As a result, European nutraceutical companies, which are generally regarded as leaders in innovation, enjoy a perception of creating the highest quality products. For example, the European approval process evaluated a total of 533 applications between 2005 and 2009. Of these, 186 applications were withdrawn during the evaluation process, and EFSA received insufficient scientific evidence to be able to assess around half of the remaining applications. Possible safety concerns were identified in relation to 39 applications. Source.

Europe also enforces stricter rules for product claims. Not surprisingly, the European market is driven on the basis of these health claims since they are harder to get. Still, there is variability from country-to-country within the EU when it comes to product claims and recommended daily allowances (RDAs). As a result, a coalition of Europe’s nutraceutical companies, including CRN, Merck, DSM and BASF, created the Food Supplements Europe (FSE) to work with regulators to ensure quality and “to shape a positive regulatory environment for the future.”

Other International Regulatory Agencies & Polices

The shift in raw material supply from the US and Europe to China and India has altered the regulatory paradigm. Without a global agency for oversight, the nutraceutical industry operates under a patchwork of national agencies with different standards and regulations. Rather than trying to police the world, national regulatory agencies generally focus on the practices and products found in their own markets while requiring local manufacturers to establish specifications for identity, purity, strength and composition for imported ingredients. However, global regulatory bodies are becoming increasingly influential within the industry. Such bodies include Codex Alimentarius, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). From the industry side, the International Alliance of Dietary/Food Supplement Associations (IADSA) works closely with international and local bodies to ensure that the views of the food supplement industry are considered in the development of policy.

Now we’ll take a closer look at the regulatory environment from key global nutraceutical markets.

Japan

Japan is a thought leader in the manufacture and use of “Foods with Health Claims” – the preferred term for dietary supplements and natural nutraceuticals in Japan. The health-conscious Japanese have long embraced the benefits from nutraceuticals, and the country ranked third in per capita spend on nutraceuticals in 2008 according to World Health Organization (WHO) data, while others place Japan as the second largest individual consumer of nutraceuticals (behind the U.S.). For regulatory purposes, nutraceuticals in Japan are generally divided into two groups. The first group, “Foods with Nutrient Function Claims,” satisfy the standards for the minimum and maximum daily levels of twelve vitamins and five minerals. Aside from these daily standards, the labels are not heavily regulated. The second group is “Foods for Specified Health Uses,” or simply FOSHU. They contain dietary ingredients that have reported beneficial physiological effects and promote health. However, like most jurisdictions around the world including the US, disease risk reduction claims are not allowed.

At present, only Foods for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) require pre-marketing approval. The multistep approval process begins when the Food Safety Commission examines the safety of the proposed product. This is followed by an evaluation of effectiveness by the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare used to give official approval, allowing the manufacturer to carry the structure/function claims and mark on the product. However, in 2009, in order to meet increasing local demand, Japanese officials created the Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA), which assumed the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s (MHLW) responsibility for the implementation of laws relating to nutrition labeling and health claims approval. Nutraceuticals World provides a helpful overview of the approval process and the role of the CAA here, and points out that nutraceutical makers can choose to opt out of FOSHU registration on the condition that their products do not bear any health claims or claim physiological effects on the human body.

Israel

Israel is considered as a key innovation hub for the nutraceutical industry. The industry is driven by ingredient companies such as Solbar Industries, LycoRed Natural Ingredients, Adumim Food Ingredients, Enzymotec, Algatechnologies and Frutarom etc. With a limited domestic market, a majority of Israel’s revenue is from exports to US and European markets. All drugs, dietary supplements and cosmetics require registration by the Ministry of Health (MoH).

China

China Health Care Association (CHCA), a government-appointed association that oversees the nutraceutical industry, estimates China’s domestic market at $15.8 billion based on 2011 sales. However, this figure only accounts for those dietary supplement products that were officially registered with China’s State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA). The US-China Health Products Association (USCHPA) believes the number is actually closer to $20 billion with the difference coming from the USCHPA’s better account of nutraceutical imports.

There are three main entities involved in policing the industry. The first is the SFDA, which is in charge of dietary supplements and issuing the “blue hat” registration. Next is the Ministry of Health (MOH), which actually oversees SFDA, but its main influence in the dietary supplement industry is overseeing the approval of new novel food ingredients; and finally, the Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) controls all of the imports and exports passing across China’s borders.

China is making some efforts to improve its notification system for food supplements. During September 2012 meetings with IADSA, Chinese health officials discussed global product placement rules, the status quo of the existing registration, and a product notification system for health food in China. IADSA Board member, Michelle Stout, commented, “The registration system in China is at present lengthy and costly, and it is widely recognized that there is a need for a more accessible system to be introduced.”

However, a much anticipated overhaul of the Chinese regulatory system has remained stalled, and SFDA draft regulations have been collecting dust since 2009. Nutraceutical World offers these three areas in need of immediate improvement:

* Change the name of the industry to dietary supplement – this would align the terminology with the international community and properly exclude products (e.g., yogurts and food products) that are being miscategorized as food supplements.

* Reform the “blue hat” system into a notification system utilizing claims based on structure function. Instead the SFDA continues to view dietary supplements akin to drugs. In doing so, its testing methods are looking for toxicity, efficacy and risk assessment, which include animal and sometimes human trials. Implementing a true notification system similar to the U.S. FDA’s DSHEA would be much easier for the government to manage. It would also be more transparent and less expensive for industry to abide by, thus increasing the amount of “blue hat” compliance and overall control of the industry by SFDA.

* Potency levels are another area that needs attention. The SFDA generally has potency restrictions that require most foreign companies to reformulate specifically for China prior to applying for a “blue hat” registration. Moreover, once the product is approved by SFDA, the formula cannot be adjusted without going through the whole two-registration process all over again. Unless backed by compelling scientific evidence, China should comply with global potency levels.

India

The manufacture, storage, distribution, sale and import of nutraceuticals in India are regulated under the Food Safety and Standards Act (FSSA) from 2006. The FSSA consolidated a collection of earlier laws (from eight different ministries) relating to food under a single set of rules relating to food and nutraceutical safety and standards. However, as this Nutraceuticals World report points out, the rules are still not in force and the government is still seeking suggestions on the draft. Some of the suggestions from within the industry call for greater manufacturing oversight – similar to those provided by Indian Pharmacopoeia – so that manufacturers of nutraceuticals comply with their safety and quality standards, thereby establishing India as a reputable supplier of nutraceuticals – much like it has in the generics sector. Like APIs for the pharmaceutical industry, India is well positioned to supply ingredients for the global nutraceutical industry, especially in the case of plant extracts and phytochemicals, where Indian companies are already establishing themselves as global suppliers. International industry group, International Alliance of Dietary/Food Supplements (IADSA), supports this view and believes India’s newly enacted regulations, when fully implemented, could boost foreign investment. In terms of domestic uptake, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) notes in a recent nutraceutical report that an improved regulatory framework to validate product claims could drive consumer demand, but for now it still lists that lack of oversight as an industry headwind.

Mexico

In Mexico, the National Association of Food Supplements Industry (ANAISA) was created in September 2011 to bring together companies in the country dedicated solely to the manufacture or marketing of food and dietary supplements. ANAISA cites a Euromonitor report that estimates the nutraceutical market in Mexico has grown by 25% in the last five years with total sales in 2011 totaling $293 million. Article 215 of the General Health Act defines dietary supplements as “herbal products, plant extracts, traditional foods, dehydrated or concentrated fruit added or not, vitamins or minerals that may arise in a pharmaceutical form and intended use is to increase total dietary intake, supplement it or replace some component of one’s diet.” According to Mexican health legislation (see COFEPRIS site), dietary supplements can not be composed solely of vitamins and minerals – in which case they are considered a vitamin drug, not a dietary supplement. Nutritional supplements may also contain substances with pharmacological action (natural or synthetic), for example, saw palmetto (plant), ephedrine, amphetamines, among many others.

As of February 2012, ANAISA consisted of nine member companies, both domestic and international, representing about 85% of the Mexican market. ANAISA works with the Mexican regulatory body responsible for food and food supplement regulation, The Federal Commission for Protection against Health Risks (COFEPRIS), and representatives of the influential scientific bodies, the National Institute of Public Health and the National Institute of Nutrition ‘Salvador Zubiran’ to oversee the advertising of food supplements. Health claims are generally not permitted for supplements, so ANAISA has worked to develop its own Code of Ethics in hopes of creating some dialogue with consumers.

COFEPRIS has recently turned its attention to non-compliant nutraceutical makers. In March 2013, health authorities seized 685,000 natural food supplements from Miracle Tonic Life companies, SRL, Natural Health and Naturism Jaguar, that made false claims about their effectiveness in curing cancer, diabetes, obesity and other diseases. In addition, COFEPRIS suspended commercial operations for not showing good manufacturing practices and failing to meet label requirements.

Brazil

According to a report by Euromonitor International, the fortified and functional foods category grew by 11% in 2010 to a total of a little more USD$6.2 billion. Similarly, the vitamins and dietary supplements category experienced growth of 12% in 2011, reaching sales of USD$1.3 billion. Also, Brazil, along with India, is the primary source for agricultural-based raw materials for many nutraceuticals, including soy for vegetable oils and soy protein.

Representing the nutraceutical industry in Brazil is The Brazilian Association of Foods for Special Purposes and Congeners (ABIAD). It works along with The Committee for Scientific and Technical Assessment of Functional and New Foods (CTCAF) to advise and lobby the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) regarding nutraceutical-related issues such as registration and regulation of new products. ANVISA generally has a broad definition for nutraceuticals, for example by introducing low recommended daily allowance requirements, and the regulatory process – whether for nutraceuticals or pharmaceuticals – can be complex and time consuming. As a result, ANVISA has recently hired additional staff and implemented electronic filing processes with the goal of reducing the time to evaluate new products by 40%. As far as health claims are concerned, Brazil established an allowable list of functional claims in 2008 for eighteen nutrients/ingredients.

Rest of Latin America

According to this 2011 Nutritional Outlook report, Latin America presents a challenge when it comes to the classification of supplements either as a food or a drug. In Brazil and Venezuela, for example, supplements fall within the food category when their levels do not exceed the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA). If exceeded, these are then treated as drugs. In Colombia, dietary supplements are treated as a different category from food and drugs. In Argentina, Chile, and Mexico, they are regulated as food. A second challenge relates to the different ingredient levels permitted in the Latin American countries, which in some cases requires different product formulas applied in order to comply with the regulations. As mentioned above, Brazil’s maximum levels are based on RDA amounts, which tend to be quite low, whereas in Colombia higher nutrient thresholds have been established. These differences make it difficult for multinational companies to penetrate the Latin American market as a whole.

The Latin American Responsible Nutrition Alliance (ALANUR) – together with the International Alliance of Dietary/Food Supplement Associations (IADSA) – have held a number of workshops throughout Latin America, most recently in Venezuela, to discuss trends in the regulation of food supplements in Latin America and worldwide, including classification and definition; the use of nutrition and health claims; the role of scientific risk assessment to establish maximum nutrient levels versus the use of Recommended Daily Allowances (RDAs); and the characteristic features of the registration and notification systems and monitoring of products once they are on the market across the globe. In Venezuela, the workshop was attended by the National Institute of Hygiene “Rafael Rangel” (INHRR) and the Ministry of Health, which are currently drafting regulations for nutraceuticals and other products bordering the supplement category.

Conclusions

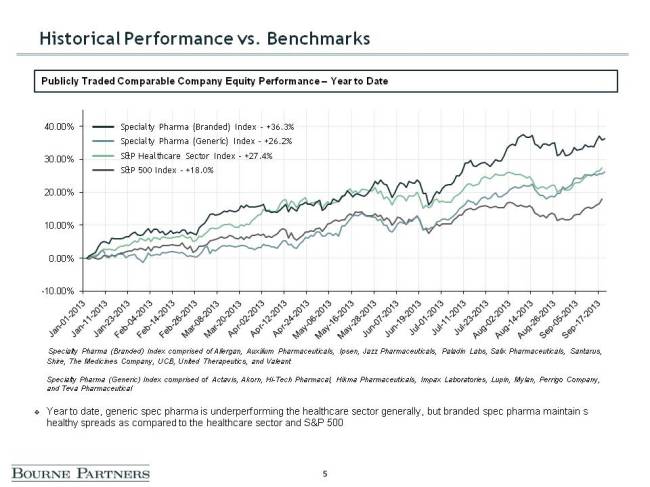

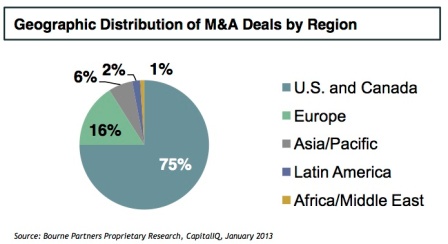

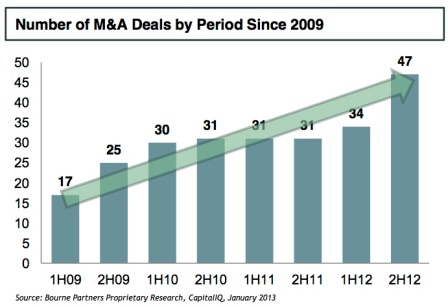

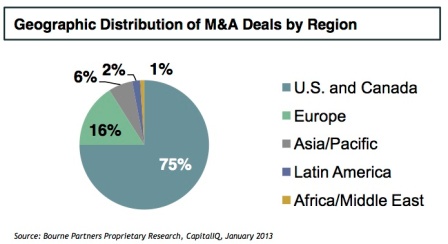

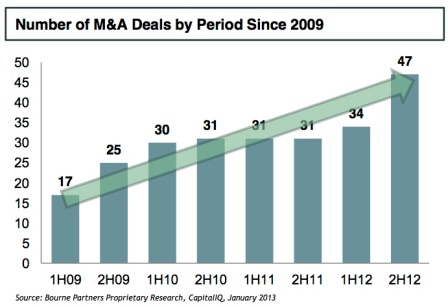

The introduction of good manufacturing practice (GMP) regulations in the US (21 CFR Part 111) ushered in a new era of regulation focused on safety and quality with the goal of identifying non-compliant suppliers, distributors and marketers through more active enforcement. With this new initiative, the impetus is on quality. As this Nutraceuticals World article points out, many nutraceutical companies are turning to audited, GMP-certified contract manufacturing firms, which have invested heavily in state-of-the-art facilities and quality infrastructure to ensure compliance. Greater enforcement of GMP regulations is a contributing force behind the current consolidation trends (see below figures) seen in the industry as nutraceutical companies seek the proper scale required to make the necessary investments to become compliant.

Sidebar: Nutraceutical Labels, Claims & Marketing

With lesser oversight than pharmaceuticals, the nutraceutical industry has taken full advantage of the Internet to offer its products to the global market, while consumers have provided an endless stream of product reviews, testimonials and even reports of adverse events – whether valid or not. Together with the multi-jurisdiction nature of the nutraceutical business, this virtual forum has created an opportunity for aggressive marketers, and a daunting challenge for federal, state and international agencies.

In order to better understand the challenge, we’ll return to a definition of nutraceuticals – this time in the context of product claims. Under US law, nutraceutical claims generally fall into three categories: health claims, nutrient content claims, and structure/function claims. Disease-related claims are generally not permitted for nutraceuticals. Instead, nutraceuticals typically claim to improve health, delay the aging process, and increase life expectancy with the following disclaimer:

“These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

And since nutraceuticals do not have to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before marketing (except for a new dietary ingredient (NDI)*), there are no clinical trials or safety data requirements, so development costs remain low as compared to the costs associated with pharmaceutical R&D. *Regarding NDIs, the FDA conducts a pre-market review for safety data and other information on new dietary ingredients (NDIs) before marketing. This is likely slowing innovation in the US since companies are required to submit safety information on any new dietary ingredient placed into products after 1994.

The minimal oversight related to nutraceutical labels and claims is perhaps the greatest difference between nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) restricted the regulation of label claims on dietary supplements by the FDA. Specifically, DSHEA allows dietary supplement labels to carry statements dealing with structure/function claims such as “supports the immune system.” However, any claims that are made must have adequate evidence to show that they are not false or misleading. The intent of DSHEA was to provide consumers access to more health-related information about dietary supplements. However, like most legislation, the Act is open to multiple lines of interpretation.

For example, what is the difference between a supplement “supporting” a normal body function as opposed to “treating a disease”? How does the FDA actually define “diseases”?

Obviously if new regulations are introduced that require the industry to prove efficacy of its products before they are marketed, the dynamics of the market would dramatically change with significant time and cost added to the development and manufacturing process. However, product labels and claims do not appear (at this time) to be an emphasis for regulators. Instead, most attention is directed to good manufacturing practices (GMPs) and ensuring consumer safety, while oversight of marketing is still largely self-policed by industry groups such as the Natural Product Foundation.

The NFP’s Truth in Advertising Program works to educate manufacturers, suppliers and retailers to help ensure that the information available to consumers is truthful and not dangerous. In the last three years, NPF initiated more than 300 advertising case reviews and mailed 235 warning letters to companies responsible for marketing dietary supplements. In 2012, NPF mailed 100 warning letters to companies marketing dietary supplements with illegal drug and disease claims. Over the course of the program, two-thirds of all advertisers contacted by NPF brought their promotions into compliance. However, with the rapid global expansion of the nutraceutical industry, there is still concern that if the abusive, misleading practices of a few non-compliant players is left unchecked, it could lead to a regulatory backlash that wipes out the relatively modest oversight currently enjoyed by the industry.